23-Feb-2017 Kleiburg is one of the biggest apartment buildings in the Netherlands: a bend slab with 500 apartments, 400 meter long, 10 + 1 stories high.

Kleiburg is located in the Bijlmermeer, a CIAM inspired residential expansion of Amsterdam designed in the sixties by Siegfried Nassuth of the city planning department. De Bijlmer was intended as a green, light and spacious alternative for the -at that time- disintegrating inner city.

The Bijlmer was designed as a single project. A composition of slabs based on a hexagonal grid. An attempt to create a vertical garden city.

Traffic modalities were radically separated; cars on elevated roads and bicycles and pedestrians on ground level. They would no longer share the same space.

Now the area houses about 100,000 people of over 150 nationalities.

The Bijlmermeer had a very optimistic start. But soon the enthusiasm for this radical residential area was overshadowed by fear-for-the-unknown. Fed by heavily economized execution, bad publicity, lack of understanding, poor maintenance and the sudden emergence of a new residential dream type -the suburban home- the Bijlmer turned into a slowly disintegrating parallel universe.

A renewal operation started in the mid nineties. The characteristic honeycomb slabs were replaced by mostly suburban substance, by ‘normality’.

However it was decided to keep the most emblematic area intact -flanking the stunning, for-ever-futuristic elevated subway line. The so-called Bijlmer Museum came into being; a compact refuge for Bijlmer Believers. Kleiburg is the cornerstone of the remaining ensemble.

Bulldoze? Kleiburg is the last building in the area still in its original state; in a way it is the “last man standing in the war on modernism”.

Housing Corporation Rochdale, however, had plans to demolish it. They calculated that a thorough renovation would cost about 70 million Euro...

But bulldozing the masterpiece by architect Fop Ottenhof would lead to a collapse of the magnificent urban composition.

In anticipation to the fierce resistance by ‘believers’ and pressure by the local government, that hoped to avert demolition, Rochdale launched a campaign to rescue the building: Kleiburg was offered for ONE EURO in an attempt to catalyze alternative, economically viable plans.

Over 50 parties responded with a range of ideas from student or elderly housing to woon/werk-units, or homes for the homeless.

Klusflat Four teams were selected to further develop their ideas. Ultimately Consortium De FLAT consisting of KondorWessels Vastgoed, Hendriks CPO, Vireo Vastgoed and Hollands Licht, was chosen with their proposal to turn Kleiburg into a Klusflat. ‘Klussen’ translates as to do it yourself.

The idea was to renovate the main structure -elevators, galleries, installations- but to leave the apartments unfinished and unfurnished: no kitchen, no shower, no heating, no rooms. This would minimize the initial investments and as such created a new business model for housing in the Netherlands.

The ambition was to open up new ways to live, to offer new typologies by combining two flats (or even more!) into one, by making vertical and horizontal connections.

The future residents could buy the shell for an extremely low price and then renovate it entirely according to their own wishes: DIY. Owning an ideal home suddenly came within reach…

Bliss By many, repetition was perceived as evil. Most attempts to renovate residential slabs in the Bijlmer had focused on differentiation, the objective, presumably, to get rid of the uniformity, to ‘humanize’ the architecture.

But after two decades of individualization, fragmentation, atomization it seemed an attractive idea to actually strengthen unity: Revamp the Whole!

It became time to embrace what is already there: to reveal and emphasize the intrinsic beauty, to Sublimize!

Interventions In the eighties three shafts had been added on the outside featuring extra elevators: although they look ‘original’ they don’t belong there, they introduce disruptive verticality. But it turned out that these concrete additions could be removed. There was still enough space in the existing shafts; new elevators could actually be placed inside the existing cores. And the brutal beauty of the horizontal balusters could be restored!

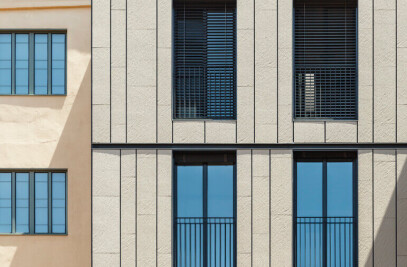

Sandblasting the painted balusters revealed the sensational softness of the pre-cast concrete: better than travertine!

Originally the storage spaces for all the units were located on ground floor creating an impenetrable area, a ‘dead zone’ at the foot of the building. By relocating the storerooms to the upper levels near the elevators the ground level could be freed up for more interactive forms of inhabitation: apartments, workspaces, daycare. As such the plinth would be activated: a social base embedded in the park.

The interior street that served as the connector between parking garages and elevator cores was a fundamental ingredient of the Bijlmer. It was located on the first floor at plus three meters and forced the underpasses to become low. And unpleasant. But since lowering the elevated roads was one of the central ideas of the renewal of the area the inner street became obsolete. Now larger openings could be created connecting both sides of the building in a more scenic and generous way.

On the galleries the division between inside and outside was rather defensive: closed, not very welcoming. There was room for improvement. The opaque parts of the facade were replaced with double glass. By opening-up, the facade becomes a personal carrier of the identity (even with curtains closed).

In addition a catalogue of facade modules was created from which the future inhabitants could choose a set of window frames that would match the customized layout of their FLATs: openable parts, sliding doors, double doors, a set-back that creates space for plants or people. As such a personal ‘interface’ could come into being that could activate the galleries.

Gallery illumination has a tendency to be very dominant in the perception of this type of single loaded apartment buildings. The intensity of the lamps that light up the front doors on the open-air corridors overrules the glow of the individual units. The warm ‘bernstein’ radiance of the apartments is obscured behind by a screen of cold lights. What if all gallery lights worked with energy saving motion detectors? Every passer-by a shooting star!

10-Dec-2012 Kleiburg is one of the biggest apartment buildings in the Netherlands: a bend slab with 500 apartments, 400 meter long, 10 + 1 stories high.

Kleiburg is located in the Bijlmermeer, a CIAM inspired residential expansion of Amsterdam designed in the sixties by Siegfried Nassuth of the city planning department. De Bijlmer was intended as a green, light and spacious alternative for the -at that time- disintegrating inner city.

The Bijlmer was designed as a single project. A composition of slabs based on a hexagonal grid. An attempt to create a vertical garden city.

Traffic modalities were radically separated; cars and bicycles would no longer share the same space.

The area houses almost 100,000 people of over 150 nationalities. In 2009 there were 140 Christian Congregations alone.

The Bijlmermeer had a very optimistic start. But soon the enthusiasm for this radical residential area turned into fear-for-the-unknown. Fed by heavily economized execution, bad publicity and lack of understanding the Bijlmer turned into a freak circus of urbanism.

A renewal operation started mid nineties. The characteristic honeycomb slabs were replaced by mostly suburban substance, by ‘normality’.

It was decided to keep the most emblematic area -flanking the stunning, for-ever-futuristic elevated subway line- intact. The so-called Bijlmer Museum came into being; a compact refuge for Bijlmer Believers. Kleiburg is the cornerstone of the remaining ensemble.

Kleiburg is the last building in the area still in its original state; in a way it is the “last man standing in the war on modernism”.

Housing Corporation Rochdale, however, had plans to demolish it. They calculated that a thorough renovation would cost about 70 million Euro...

But bulldozing the masterpiece by architect Ottenhof will lead to a collapse of the magnificent urban composition: an unbearable thought.

In anticipation to the fierce resistance by ‘believers’ and pressure by the local government, that hopes to avert demolition, Rochdale launched a campaign to rescue the building: Kleiburg was offered for ONE EURO in an attempt to catalyze alternative, economically viable plans.

Over 50 parties responded with a range of ideas from student housing to woon/werk-units, to homes for the homeless.

Four teams were selected to further develop their ideas. Ultimately Consortium De FLAT consisting of KondorWessels Vastgoed, Hendriks CPO, Vireo Vastgoed en Hollands Licht, was chosen with their proposal to turn Kleiburg into a Klusflat. ‘Klussen’ translates as to do it yourself or ‘doing odd jobs’.

The idea is to renovate the main structure -elevators, galleries, installations- but to leave the apartments unfinished and unfurnished: no kitchen, no shower, no heating, no rooms. This minimizes the initial investments and as such creates a new business model for housing in the Netherlands.

The future residents can buy the shell for an unprecedentedly low price and then renovate it entirely according to their own wishes: DIY. Owning an ideal home suddenly comes within reach…

The ambition is to open up new ways to live, to offer new typologies by combining two flats (or even more!) into one, by making vertical and horizontal connections.

Many attempts to renovate residential slabs in the Bijlmer, Kleiburg in particular, have focused on differentiation, the objective, presumably, to get rid of the uniformity, the repetition, to ‘humanize’ the architecture.

After two decades of individualization and fragmentation and atomization it seems an attractive idea to actually strengthen unity: Revamp the Whole!

It is time to embrace what is already there, to emphasize the intrinsic beauty. Sublimize!

In the eighties three shafts have been added including extra elevators: although they look ‘original’ they don’t belong there, they introduce disruptive verticality. But it turns out that these concrete additions can be removed. There still enough space in the existing shafts; the elevators can actually be placed inside the existing cores, the brutal beauty of the horizontal balusters can be restored.

The current division between inside and outside is defensive: closed, rather unfriendly. There is room for improvement. Can we imagine opening-up the facade to create a ‘border’ that is more inviting?

The idea is to create a catalogue of facade modules. The future inhabitants will be able to choose a set of window frames that matches the customized layout of their FLATs: Openable parts, sliding doors, double doors, a set-back that creates space for plants or people. As such a personal ‘interface’ will come into being that will activate the galleries.

The new facade will be made of wood, it will be tactile. The facade design creates a ‘filter’. It aspires to render a form of harmony, or homogeneity; the assembled individuality remains coherent.

In the age of iPad, ‘abstraction’ can make a comeback. Kleiburg’s minimal ‘hardware’ is already magnificent. And now the ‘interface’ has the chance to become diversified and personalized.

One of the central ideas of the renewal of the Bijlmer was to lower the elevated roads and to demolish the multi-story parking garages. From now on cars will be introduced on ground level. This means sacrificing the most positive feature, the green space. A devilish dilemma…

The zoning law prescribes the parking to be positioned directly next to the building. Can we explore a more generous direction? What if we examine which trees are valuable and ‘bend’ the road around them to create a parkway with the elegant curves of a race track? Zocher meets Zandvoort: a combination of park and parking.