This project entailed the refurbishment of a tired 1950’s ground floor flat to create a full-time residence for a young family of three and two dogs. Collectively, we set out to create a series of design interventions that would imbue the interior with a sense of calm, while subtly referencing the home’s coastal setting.

Our clients made the choice to live in this compact, two-bedroom unit because of its proximity to surf breaks, fishing spots, family and the local pub. We note that no order of importance in this list was disclosed! Having lived in various parts of Australia and the US, they jumped at an opportunity to acquire the property while renting another unit within the complex. Growing up in Portsea, Lachlan had spent much of his life surfing and fishing the coastline, so the locality of the property and the lifestyle it enabled had huge appeal.

The refurbished shack is one of eight single level dwellings in a complex known as Harbour Gate, which has rear access to Portsea Beach and “Millionaires’ Walk” - a green strip of public land between Port Phillip Bay and some of the Mornington Peninsula’s most sought after real estate. The strip is used by residents of Harbour Gate to access to the local pier and the iconic Portsea Hotel.

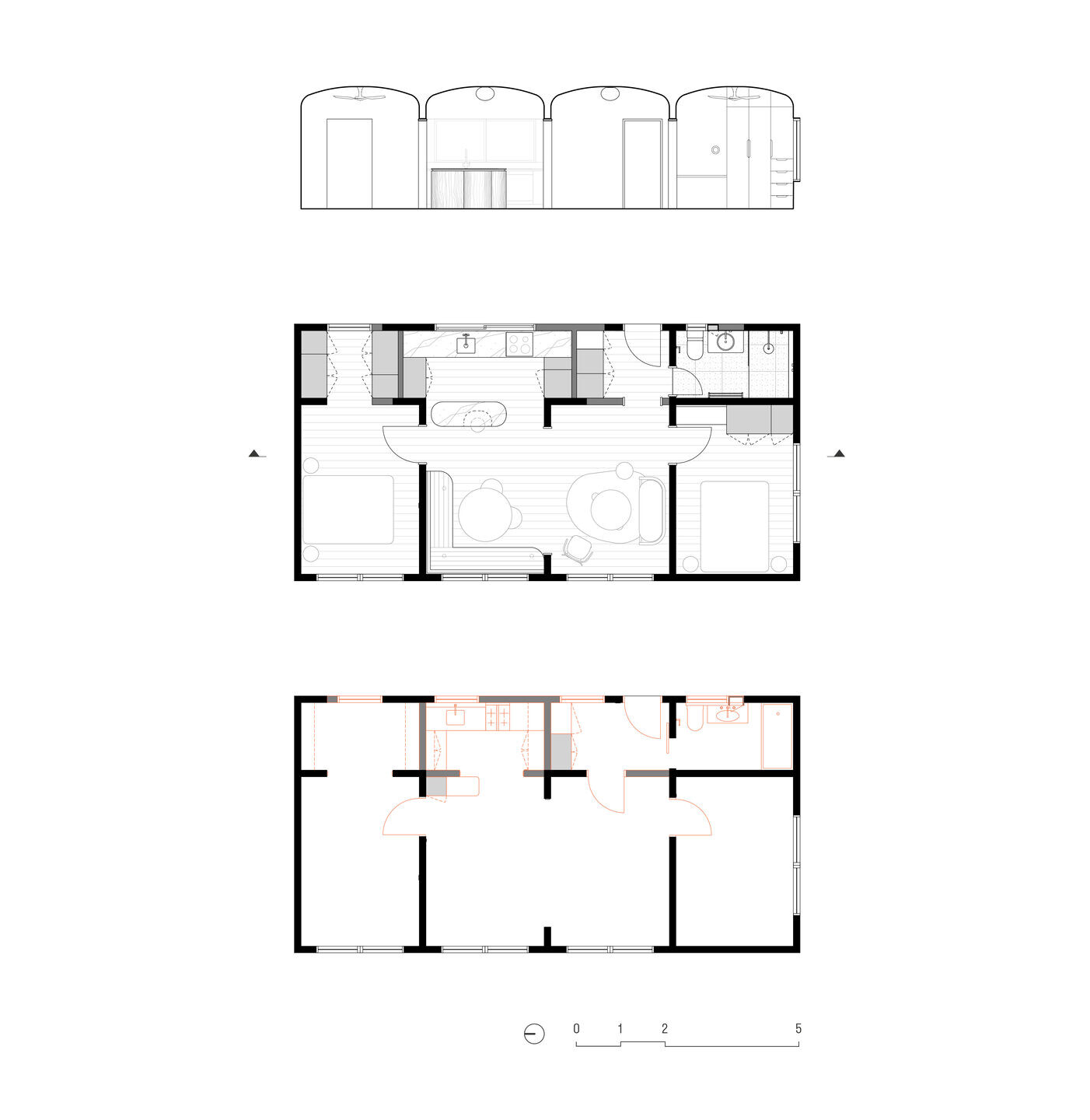

Harbour Gate is the only remaining example of an experimental prefabrication system developed by architect Sir Bernard Evans in 1948, as a government-backed solution to the post-war housing crisis. While appearing somewhat unassuming from the outside, each unit is comprised of eight reinforced plaster domes, craned into place and then covered with conventional construction techniques. It is unknown to us why this building system was short-lived, but the internal volumes and curved plaster were seen as an asset to the project - one that we set out to enhance.

The assembly of the original structure resulted in a plan that is segmented into discrete rooms or zones, with each space articulated by a domed ceiling. The new components of the house drew upon this sense of separation, presenting as a series of individual furniture-like elements. For example, the kitchen island is curved at its corners and is detached from the wall. The banquette seat is another element that defines the edge of the dining zone. Similarly, the bathroom vanity features round legs with a stone top – something more akin to desk furniture than to bathroom vanities. The threshold to each zone is trimmed with new timber reveals, articulating each building module as one moves through the home.

The clients expressed a desire for a simple material palette that was ‘of place’ - a coastal interior that was not kitsch or overtly referencing the beach (we note in the naming this project we failed in this regard!) A key design move was the selection of an internal paint finish for the plaster domes and walls. A breathable lime-based paint with a subtle texture unifies the segmented plan and enhances the sculptural quality of the domes, a three-dimensional surface that dynamically changes with varying light conditions over the course of each day and season. The paint also serves a functional purpose because it allows the retained plaster to breathe, which improves the longevity of the original material as well as improving internal air quality. Much like a sandy shore is the backdrop to the ocean, the sand-coloured paint finish forms the backdrop of the house, giving the individual elements a sense of legibility within the home.

Another important choice was the limestone kitchen bench – evoking imagery of fossilized shells, but also a nod to Portsea’s history of limestone quarrying and construction. The cabinetry colour is a muted interpretation of the local coastal tea-tree scrub that populates the dunes as well as the common areas of the apartment complex. These muted green and sandy tones are carried through to the bathroom with handmade tiles and terrazzo, creating an idyllic place for a post-swim rinse.

When we first visited the site, the clients took us down to the Bathing Boxes on the Portsea Front Beach, one of which was owned by a friend of theirs. The timber stud walls inside the beach box were left unclad, which meant that the noggins could be used as shelving for spools of fishing line, bottles of tomato sauce, sunscreen, and tanning oil. We discussed with the clients about how, with a little bit of ingenuity, a compact space can be fulfilling and functional. The bathing box demonstrated an ‘essential’ kind of living. When we reflect on the project, the ethos of this simple structure was translated to our clients’ home in both a functional and aesthetic way.

The rigidity of the original plan meant that the smaller dome modules had provided more than ample space to some areas – and limited the functionality of others. The reconfigured kitchen borrows area from what was previously a much wider entry vestibule on one side and a generous walk-in-robe on the other. This redistribution of only a few square meters ‘unlocked’ the kitchen – and made it possible to prepare family meals, where previously the kitchen was comparable to something found in a mobile home.

The most significant sustainability agenda in the project was a collective choice avoid an extension to the rear of the unit and to retain as much of the existing structure and services as possible. The home was “electrified” in the construction process, and low VOC paint, laminate and flooring were specified. The clients opted to rely purely on ceiling fans, cross flow ventilation and external shading in summer for passive cooling. Electric heating panels have been fitted, with a solar PV array install forthcoming.

As with every project, budget was a key challenge. Luke Burns of LUBU Building connected us to the owners, and he was instrumental as a collaborator in managing budget from the outset. This involved testing design options as well as enabling us to source local trades, or request pricing from multiple sub-contractors. This was particularly beneficial in a time where construction costs were increasing dramatically.

In summary, Portsea Surf Shack is the thoughtful reimagination of a historic structure, through a series of restrained, elemental interventions. Through careful material selection and economic use of joinery, this compact seaside shack has been completely revitalised, demonstrating that adaptive re-use of old apartment stock forms an important part of residential regeneration.