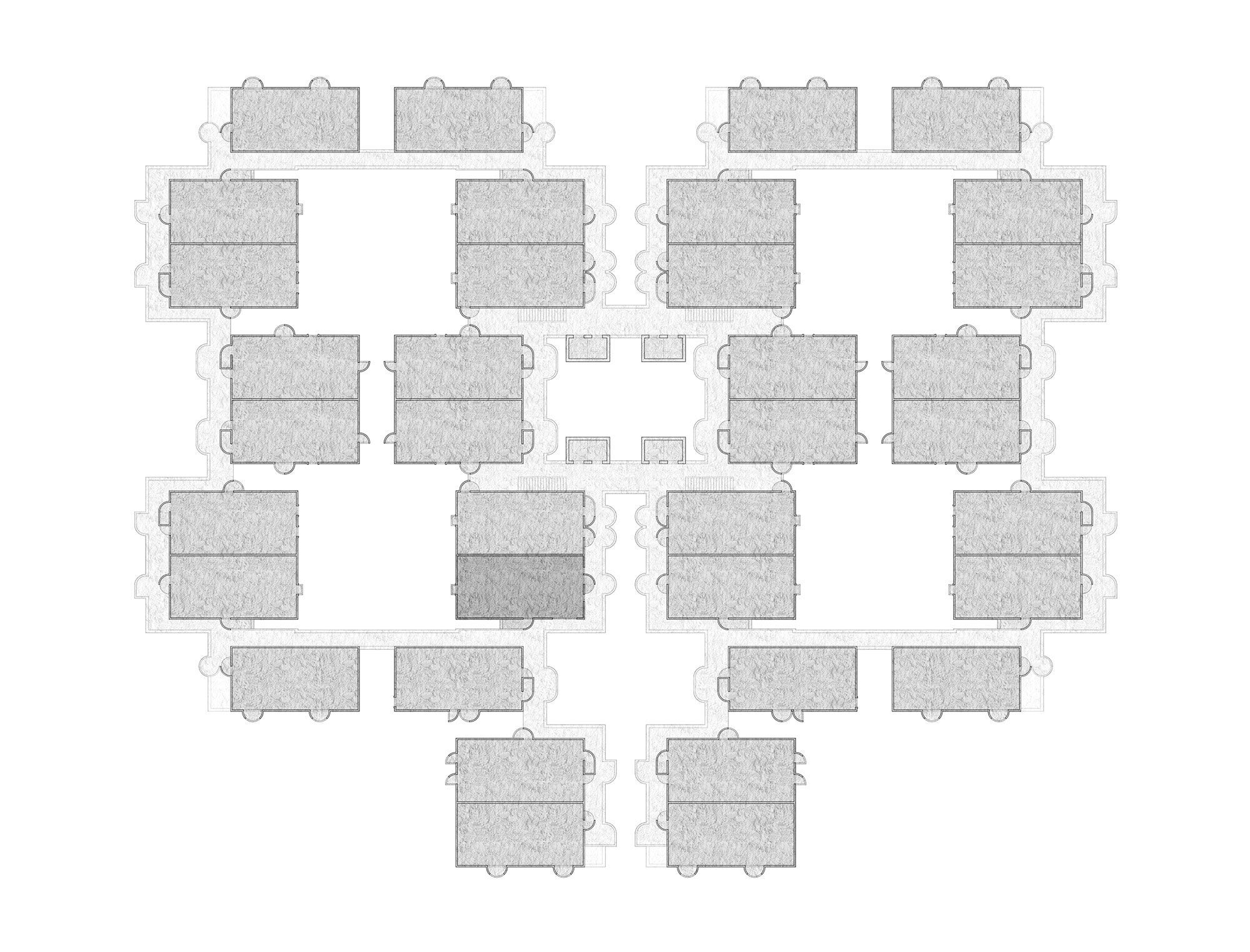

The project of Walden-7 (1973-75) in Sant Just Desvern (Barcelona) is the culmination of the experimental urbanism Ricardo Bofill developed during the 1960s and 70s in various places of the Spanish geography. The series of projects built in Sitges, Reus, and Calpe, along with the failed utopia of the City in Space in Madrid, concludes with the construction of Walden-7, the most ambitious of his projects until that point, but also the most polemic: the problems derived from its construction extend over time, to the point in which the demolition of the whole building is considered in the 1980s. Finally, and after a costly intervention, the building is listed as a heritage asset.

In a moment in which the restoration of existing structures is seen as a necessary step towards a more sustainable balance of our planet's resources, the project for the refurbishment of one of the building's 446 apartments presents the added question of how should we deal with contemporary architectural heritage. This is a building so recent that its authors not only still live; they are also still active in their profession. And this is, at the same time, a work of architecture which after decades of oblivion, it is currently reviving due to its photogenic presence in social media and an ambition to recover a certain experimental spirit in architecture: some times from a social, urban, or playful background, other times from the purely aesthetical.

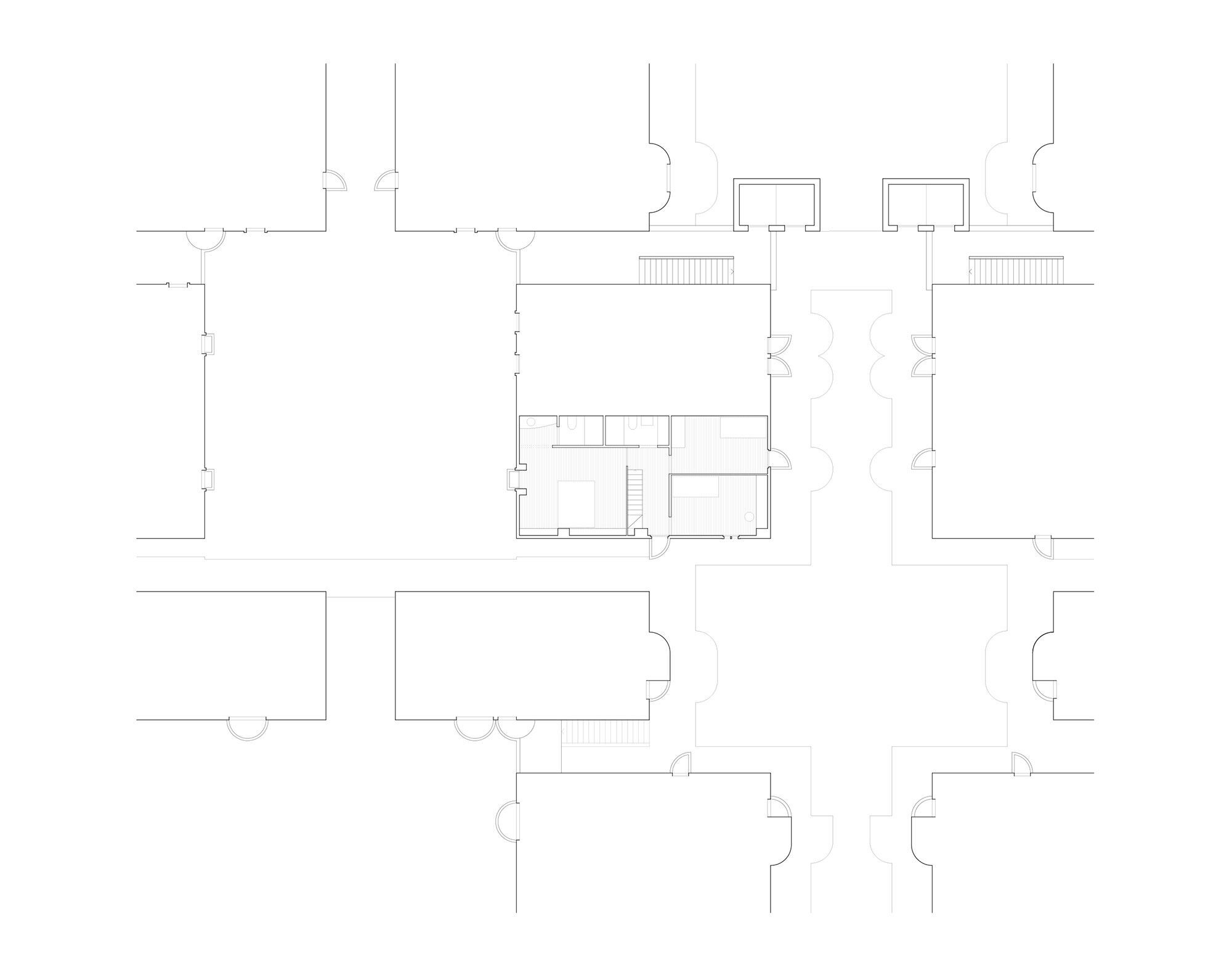

Four modules developed in two floors define this dwelling situated in the levels 12th and 13th of the building. The ground floor is transformed into a large open space, while the bedrooms are placed in the first floor. In this project, however, it is more important to talk about context and about language, than it is to discuss the configuration of its spaces. Located in the central part of the complex, its belonging to the building is practically inescapable, even in its interior. Every one of the apartment's windows frames fragments of Walden-7. Light comes in shaded in turquoise in the northern rooms, more reddish in the south.

In this context it was essential that our intervention established a connection with the rich fabric of Bofill's architecture, but without trying to mimic it. The project introduces flashes of colours from the outside in: brick red, dark blue, and sand. The topographies that Bofill envisioned for the interior of the apartments, but which were rarely built, are re-thought and adapted to the needs of the new owners and future users, with wide benches that turn into sofas, that end up connecting with the existing staircase, which is kept in its upper steps, only painted. The stepped geometry appears in the laying of the two-toned tiles in the bathrooms. And the circle shape, so ubiquitous in the configuration of the building and its morphology, materializes in various ways: the red step, the lights, the arched divisions, or the mirrors.