Welcome to the Archello Podcast, architecture’s most visual podcast series. Listen as Archello's Paris-based Editor in Chief, Collin Anderson, sits down with architects to discuss their careers and projects. Each audio episode is accompanied by a rich visual storyboard which listeners can use to follow the discussion. This episode is made possible by support from Kingspan Group.

Introducing Daniel Lobitz, partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects

In this episode, Archello connects with Daniel Lobitz, partner at

Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA), a firm known for its contextual designs that reference history and place, especially for projects in the office's hometown of New York City.

Since joining the firm in 1986, Lobitz has led transformative projects across the country, including the tallest residential tower in Lower Manhattan at 30 Park Place, One Bennett Park in Chicago, and the reimagined Lovejoy Wharf in Boston. His work spans from large-scale urban developments to award-winning product design, with a focus on creating spaces that enhance the public realm.

Listen and scroll as Lobitz discusses the evolution of multifamily residential design and the enduring importance of context in architecture.

Inside RAMSA's Park Avenue office, New York City

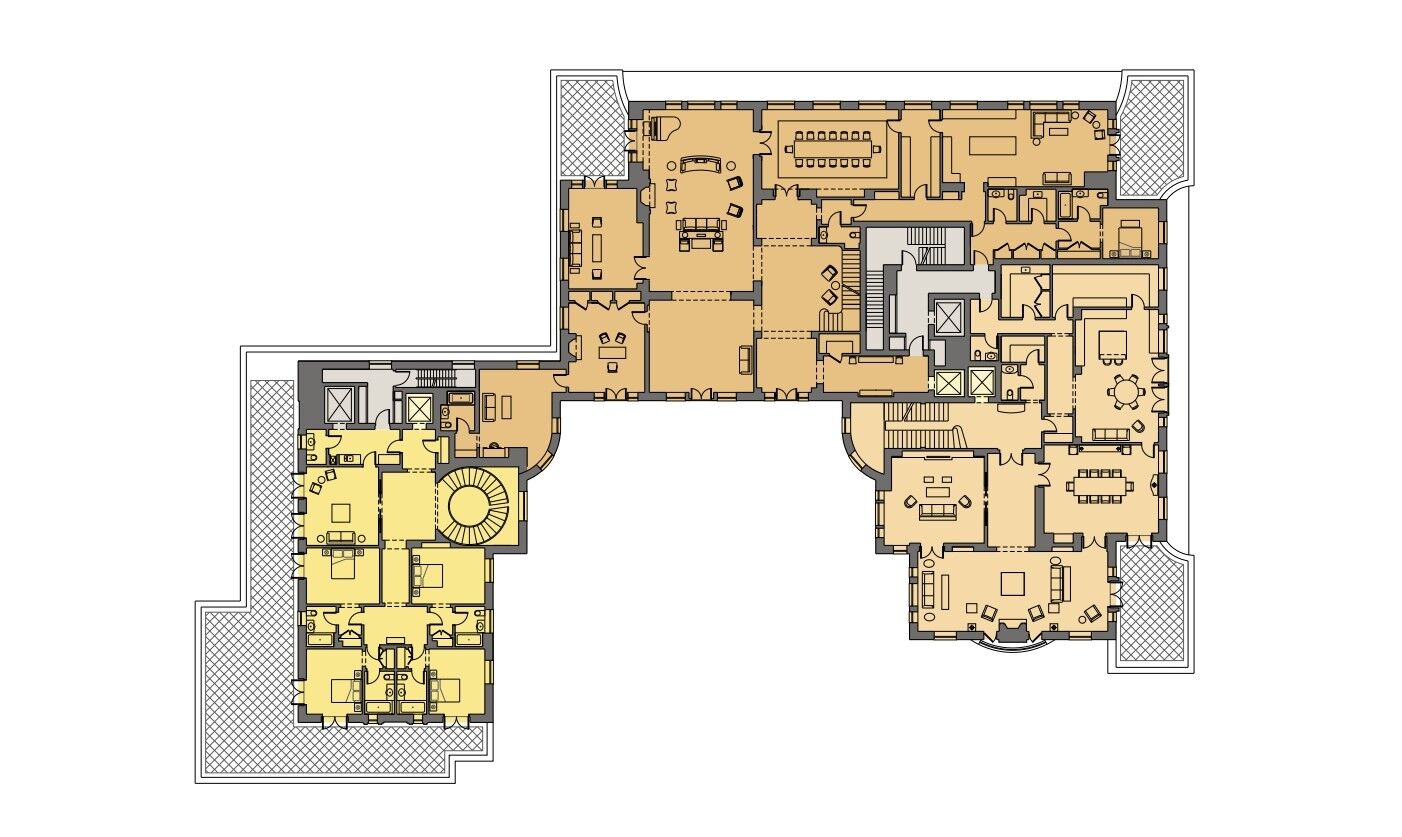

RAMSA's office is steeped in a certain academic character with a spacious, library-focused design and an open-plan culture with diverse teams. The firm moved locations six years ago and, according to Lobitz, the new office captures many of the same design strategies with a warm, knowledge-centered environment.

It is an environment conducive to learning which underscores a priority that RAMSA places on cultivating young architects. Its internship program, which used to pull students from universities that RAMSA’s partners had attended, has expanded its approach, building relationships with more schools and participating in initiatives like the National Organization of Minority Architects’ program to recruit a wider, more diverse talent base.

On joining RAMSA in the 1980s

When Lobitz first began at RAMSA the office consisted of about forty people. At that time, Robert Stern was the sole owner, and there were no partners. Lobitz had just graduated from Columbia University in 1986 and was at home working on a portfolio when, unexpectedly, a friend called with a short-term offer from Stern's office. “They needed someone to help with a house in New Jersey for about two weeks.” Like many success stories, that temporary arrangement quickly shifted. Decades later, Lobitz is still at RAMSA and has helped it grow into a celebrated global practice.

Asked what made them stay, Lobitz references the immediate sense of trust. Even as a newcomer, he was given a small design project—creating a built-in bench. That gesture encapsulated a consistent RAMSA practice: let promising designers “flex their design skills” from day one. The firm offered an environment far too compelling to leave: “Our approach is to design buildings that really grow out of their specific place, that really grow out of history, that we study precedent,” says Lobitz.

On his lifelong fascination with housing

Lobitz describes an early obsession with home plan books found at supermarket checkouts. That childhood interest in floor plans and “fantasy house sketches” inevitably led to focusing on housing projects. Residential architecture, he notes, forms the foundational thread of cities—“the genesis of architecture.” It is what gives places like New York their character, through the historic brownstones, the brick townhouses, the limestone apartment buildings, and the way they line up along city blocks.

"Human shelter is really the genesis of architecture...and so the fabric of any significant city or town is really largely residential."

“What you think of when you think of New York … is the organization of the streets and blocks, the brownstones, the tenement buildings, the apartment houses,” says Lobitz.

Residential design poses the challenge of integrating personal comfort, privacy, and flexibility. In New York City, that challenge is multiplied by density, zoning, and the city’s signature architectural lexicon. Over the last few decades, the housing market in Manhattan has shifted toward a desire for both historical continuity and modern innovation—particularly in the luxury sector.

On 30 Park Place, New York City

One of RAMSA’s most prominent residential projects is 30 Park Place, which overlooks the southern tip of Manhattan in close proximity to the Woolworth Building. At 82 stories, it is the tallest residential building in Lower Manhattan, combining private condominiums with a Four Seasons hotel.

The client here, according to Lobitz, "saw the need for a hotel and residential component downtown, where people had begun moving back in the 1980s … but this was the first really big luxury building in New York.” For Lobitz, 30 Park Place was the first major tower project he led, alongside other longtime RAMSA colleagues, Robert Stern, and co-partners. The team studied Lower Manhattan’s original skyscraper tradition, referencing bold office towers by architects like Ralph Walker, as well as grand hotel-apartment hybrids in midtown—The Sherry-Netherland, The Pierre, and The Waldorf Astoria. The result is a building that merges a classic sense of proportion, ornament, and materiality with a distinctly modern vertical presence.

“We looked at the great buildings of the early twentieth century in New York, but we needed to re-interpret them for how people live today … more open, more flexible, while still celebrating the romance of a setback tower.”

The tower’s façade is rendered in Indiana limestone and precast concrete panels, a nod to the iconic stone that has clad some of New York’s most revered buildings. As Lobitz points out, the mix of genuine limestone and high-quality precast also serves practical construction needs for a 900-plus foot tower. Windows are often installed in the panels off-site, brought to the site, and lifted into position—a significant logistical feat.

Lobitz has a Bachelor’s in Hotel Administration from Cornell, and that background continues to shape his approach to multifamily projects. There is a “hospitality aspect” in designing for large numbers of people in one building, layering in staff components, amenities, and privacy. 30 Park Place, with its hotel-condo stack, epitomizes that union: there are separate entrances and lobbies, private amenities, and subtle connections for residents who want to enjoy the hotel’s bar, restaurant, and spa without public exposure.

On 150 East 78th Street, Upper East Side

Switching to the Upper East Side, Lobitz describes the project at 150 East 78th Street as a more explicitly classical design. The neighborhood’s mid-twentieth-century reputation as Manhattan’s most elegant enclave made the project both exciting and challenging. “We really tried to design something that fit in. We picked up on the tradition of limestone apartment houses,” he says.

Here, arches, ionic pilasters, and classical rhythms evoke a timeless New York atmosphere. Green-painted metal pavilions crown the stepped upper floors, inspired by the neighborhood’s distinct references to conservatories, townhouse rooftop gardens, and greenhouse additions. That crisp green metal stands in gentle contrast to the building’s stone, linking it to the local architectural typologies in a fresh way.

Lobitz notes that while older New York apartment layouts often assumed in-house staff would occupy multiple small bedrooms and enclosed kitchens, today’s residents live more openly. RAMSA retools historical inspirations—like formal entry sequences or carefully scaled window groupings—to suit the contemporary need for flexible rooms and integrated family spaces. Still, the firm preserves a sense of tradition and proportion that aligns with the “DNA” of the Upper East Side.

On refining building forms in New York City through zoning and setbacks

Just as important as façade treatment in Manhattan is the question of how a building rises. The classic “wedding cake” massing or a series of setbacks results from zoning rules that have, in turn, influenced the city’s stylistic identity for generations. “A setback is an opportunity to create a penthouse apartment,” says Lobitz.

He explains that each floor where the building steps back can provide a valuable private terrace. At 30 Park Place, for instance, there are eight full setbacks and double-height loggias—each a desirable penthouse condition with sweeping city views. The architect’s task is to ensure that these setbacks feel coherent from the skyline perspective but also deliver functional value to residents inside. Ultimately, these top floors remain some of the most coveted—and high-priced—units in Manhattan.

On Abington House on the High Line

RAMSA’s Abington House is located in a rapidly transforming industrial neighborhood near the northern curve of the High Line in West Chelsea. This stretch of Manhattan has shifted significantly over the years, prompting architects and developers to seize on the popularity of the High Line’s pedestrian promenade.

“That building is very close to our previous office—just a three-minute walk—and I could see the entire site from the window,” says Lobitz. Unlike 30 Park Place or 150 East 78th Street, Abington House departs from limestone, opting instead for red brick and dark metal details. This evokes the industrial vernacular of the surrounding low-rise warehouses and the High Line itself. At the same time, it is fundamentally residential, with thoughtful window spacing and warm materials that invite a sense of home.

“We picked up on the red brick from the old industrial buildings, used black metal referencing the High Line, and then carefully shaped it into a new kind of tower with setbacks,” explains Lobitz.

As visitors and residents walk the High Line, Abington House stands as a prominent visual anchor: the building mass ends the view corridor where the elevated park curves west at 30th Street. The shift from factories and warehouses to high-end housing—featuring bright amenities, polished lobbies, and scenic roof decks—mirrors how New York continues to adapt.

On One Mayfair in London

While RAMSA is strongly identified with New York City architecture, the firm’s international portfolio extends to Europe, Asia, and beyond. One Mayfair marks a significant move into the heart of London’s storied West End, a neighborhood shaped by four centuries of urban evolution.

Lobitz recalls how Mayfair historically comprised seven great estates, subdivided and built up over time with Georgian rowhouses, Victorian expansions, and a handful of pre-World War II multifamily residences. RAMSA’s in-house library had long featured English precedents—Robert Adam, John Nash—so the architects had a foundation, but the team still conducted in-depth research into the immediate surroundings of their specific Mayfair block.

“We turned to Portland stone, which is the limestone of London. Many significant buildings—civic and residential—are built with it, so we wanted to pick up on that local tradition,” says Lobitz.

One Mayfair aims to be the “most luxurious residential building in Mayfair.” With 29 units spread over roughly 225,000 square feet, each apartment averages around 7,000 square feet—unusually large for London. As Lobitz points out, new UK regulations likely won’t allow future residential units on that scale. This project includes an array of amenities: a private motor court, individual pools in many penthouse units, a communal spa, private wine rooms, and “show garages” where car enthusiasts can sit in lounge chairs next to their prized automobiles.

The site configuration also allows for a newly created public square, featuring artwork accessible to the entire neighborhood. Much like RAMSA's best-known New York projects, Lobitz underlines the importance of shaping not just private interiors but also the streetscape and civic identity.

“It’s one of the exciting things about big multifamily projects … you often have an opportunity to make a significant contribution to the public realm.”

If there’s one striking difference between London and New York processes, Lobitz explains, it’s speed. A New York multifamily tower can go from design to completion in as few as three years for moderately tall buildings, or four years for "supertall" buildings. One Mayfair, by contrast, was initiated in 2011 and will likely complete in 2027—sixteen years in the making.

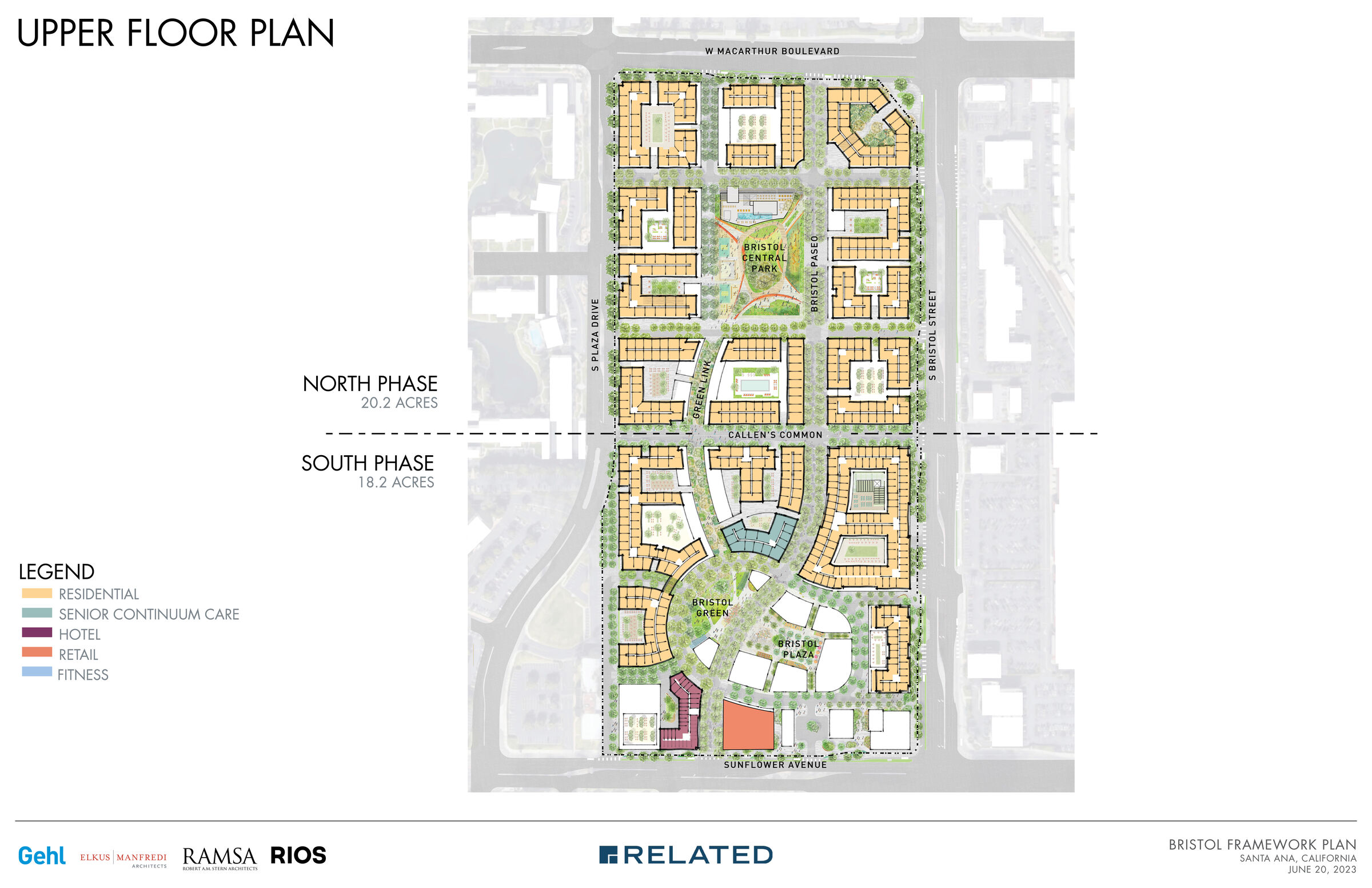

On master planning in Southern California

RAMSA’s reach extends beyond dense urban towers to more open-site planning, as demonstrated by an ongoing project in Santa Ana, California. In this location, car culture is strong, and city blocks are shaped more by roadways and parking than walkable neighborhoods. Nevertheless, Lobitz views that challenge as an opportunity to build a new urban heart:

“We tried to create a new center for Santa Ana—true mixed-use with streets, parks, a hotel, office space, senior living, and residential.”

Refining the massing, circulation, and phasing plan ensures the development can be built in discrete parts while still appearing complete and unified. Parking remains a core question, but the firm’s strategy is to conceal it and reduce its dominance over the streetscape. The end goal is an environment that remains welcoming to vehicles yet rebalances public space, so pedestrians and families can enjoy a more walkable, livable district.

On product design

“We like to say at RAMSA that we design everything from towns to tabletops,” says Lobitz. RAMSA’s longstanding tradition of crafting furnishings, lighting, and fixtures for its own projects reflects a deep-seated desire to create cohesive environments. By collaborating with manufacturers like Calista by Kohler, Lobitz leads development of custom faucets, sinks, and bathroom suites that are then often specified in RAMSA buildings.

Product design, according to Lobitz, is "an opportunity to expand your reach and influence, because these products are sold broadly.” He highlights how Frank Lloyd Wright and others before him designed entire sets of silverware, chairs, and even china to ensure that the building’s aesthetic extends down to the smallest details. In the case of RAMSA, product lines that start as custom solutions for a single project can become bestsellers with a global audience. Lobitz notes that RAMSA’s bathroom fixtures quickly rose to become one of Calista’s top-selling collections.

By weaving product design into architecture, RAMSA underscores the notion that spaces are formed at every scale—from the silhouette of a skyscraper against the skyline, to the handle of a faucet in a master bath. Lobitz notes his belief that this holistic approach not only serves clients but also enriches the profession, ensuring that design remains both refined and human-centered.