Making use of a stacked series of prefabricated hotel units as well as cores in cross-laminated timber (CLT), White Arkitekter has realized one of the world's tallest timber buildings in northern Sweden. The construction knowledge of the regional forest industry, complemented by recent developments in CLT technology, played an important role in engineering the innovative high-rise structure.

“The city of Skellefteå is situated near to the region’s timber and mining industries,” says Robert Schmitz, lead architect for White Arkitekter’s Sara Cultural Centre project. Schmitz was involved in conceiving the 30,000 square meter proposal for the complex in mass timber, the winning scheme submitted to an open competition in 2016. “Our take on the project was to create a sustainable building with local materials. You dig where you stand, so to speak.”

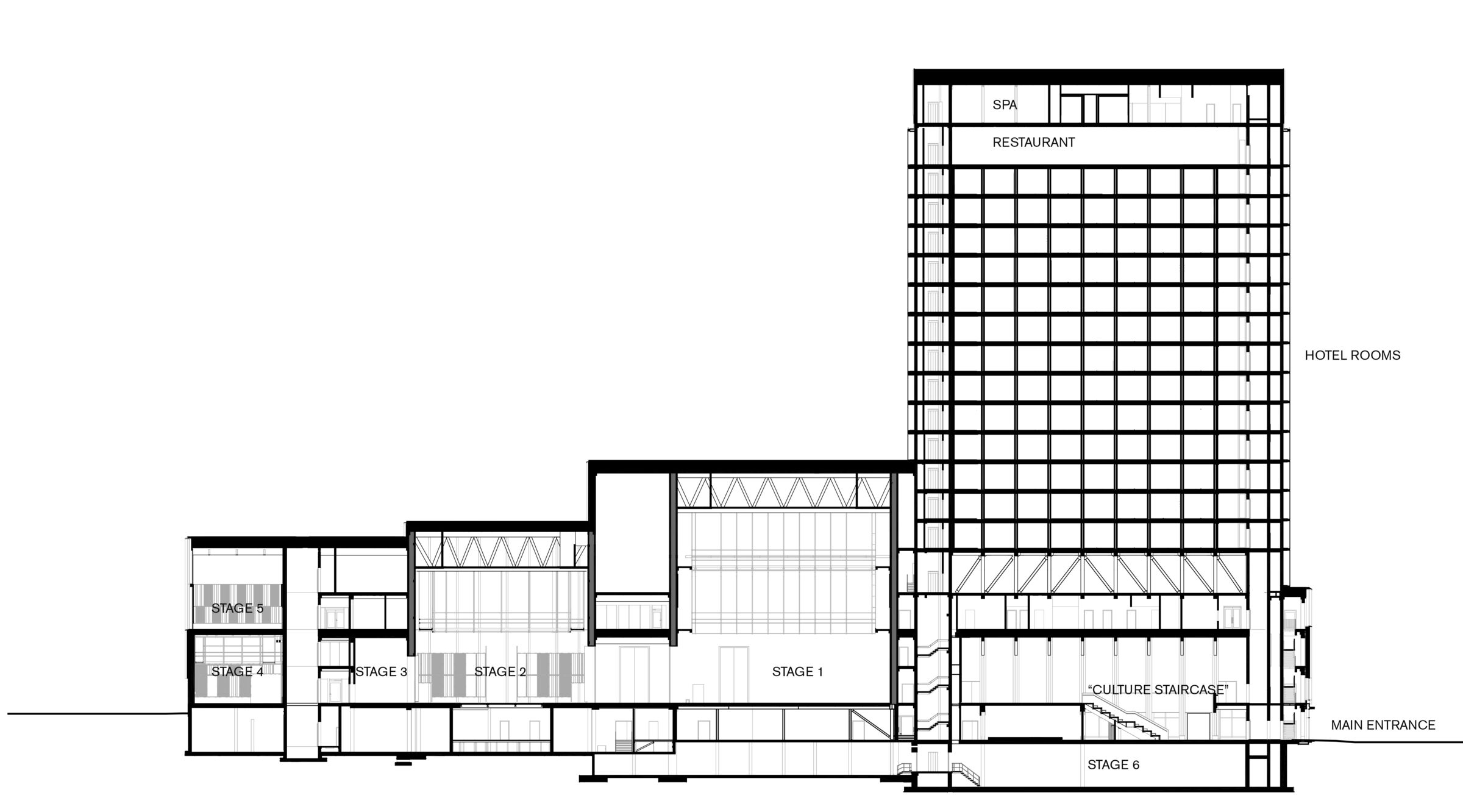

The public project was completed in 2021 and houses venues for arts, performance and literature. The complex also contains a new hotel tower to support the city’s growing tourism industry and provide the municipality of Skellefteå with a source of revenue.

Schmitz and his team, which work from White Arkitekter’s Stockholm office, chose to pursue the project with a timber structure due to the supply of regional forests, access to local sawmills and fabricators knowledgeable in timber construction. “Being from Stockholm, a 20 story hotel didn’t seem so tall,” says Schmitz. “Though we ended up more than doubling the height of the tallest timber building in Sweden at the time, which was eight stories.” The city of Skellefteå consists of predominantly low-rise buildings, according to Schmitz, and there is no regional limitation on building height.

The competition consisted of six weeks of intense schematic design work during which CLT seemed like an ideal solution for the program. “But then, when we won, we were actually a little afraid of a CLT shortage,” says Schmitz. Only a small local CLT factory with limited output existed. Though an alternate hybrid timber-concrete proposal was also considered for the project, it was ultimately more efficient to produce the entire building structure in timber once the contractor was engaged. The selected CLT factory eventually expanded its production capacity during the design process specifically to meet the project demands.

CLT versus glulam

CLT is a structural engineered wood product manufactured through a process of planing, gluing and pressing together multiple layers of solid-sawn lumber, each layer oriented perpendicular to those adjacent to it, to achieve structural rigidity in two directions. Like an enhanced plywood, CLT panels are laminated and can range in thickness based on the number of layers used. Despite its mass-market availability and use today, CLT is a relatively new product, only gaining traction in Europe in the early 2000s and then later in North America. Standards for CLT use in construction were first incorporated into the International Building Code in 2015.

CLT is not to be confused with glued laminated timber (glulam), another popular mass-timber product type in which all laminations are orientated in the same direction. While both products are structural in nature, CLT is typically used for building surface elements such as walls and floors; glulam, on the other hand, is typically used for load-bearing framing such as rafters, beams and columns. Glulam products were developed earlier and used widely in European construction from the early decades of the twentieth century.

Collaborating with Norway-based structural engineers Florian Kosche, White Arkitekter developed two different timber construction systems for the project: one for the cultural center podium, and a second for the high-rise hotel. The 75-meter tall, 20-storey tower is constructed of prefabricated CLT modules stacked between two elevator cores also entirely made from CLT. The low rise portion of the building consists of a timber frame with pillars and beams made of glulam, while cores and shear walls make use of CLT and help to redistribute loads from the tower.

CLT is a renewable material using timber cut from trees that naturally remove carbon from the atmosphere throughout their growth. And, seemingly like all mass-timber products, CLT is becoming an increasingly popular construction material due in part to its lower embodied carbon footprint. Though the availability of CLT puts it, economically speaking, in fair competition with concrete and steel in some countries, it still remains out of reach in many others: where access to forests or to purpose-built factories is limited, for instance, or where CLT must be purchased and shipped from abroad. Whether possible future taxes on embodied carbon tip CLT to the side of being more economical than concrete and steel, only time will tell.

CLT is typically made from larch, pine or spruce and must be harvested in a specific, regulated manner to guarantee its viability as a sustainable material. Requirements include using timber sourced from forests that replace cut trees and also maintain lengthy growing periods. All timber for the Sara Cultural Centre, according to Schmitz, is FSC-certified spruce locally sourced within a radius of 120 kilometers from the project site.

In addition to being renewable and green, CLT panels benefit building projects in a number of other ways. Because they are fully fabricated prior to transport, construction times are reduced as on-site cutting and sizing are unnecessary. The product’s design is also flexible and panels can be variously sized as required for walls, floors and roofs.

The material properties of CLT make panels airtight and thermally insulated. CLT is also lightweight, can be used as a structural element and can meet certain fire ratings. Fire code legislation in Sweden measures performance rather than being specific to material. White Arkitekter, which has worked on a significant number of timber buildings, was able to pull from its experience to detail much of the mass timber used in the Sara Cultural Centre to meet these performance requirements.

An innovative high-rise structural system

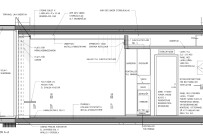

The Sara Cultural Centre programme called for several innovative solutions to handle spans, flexibility, acoustics and loads. A flexible open ground floor was required for the project and led to the tower structure essentially being designed as if on stilts. A three-story cavity at the main entrance is topped by a technical floor with plant rooms where hybrid steel trusses transfer loads from above.

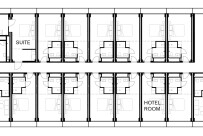

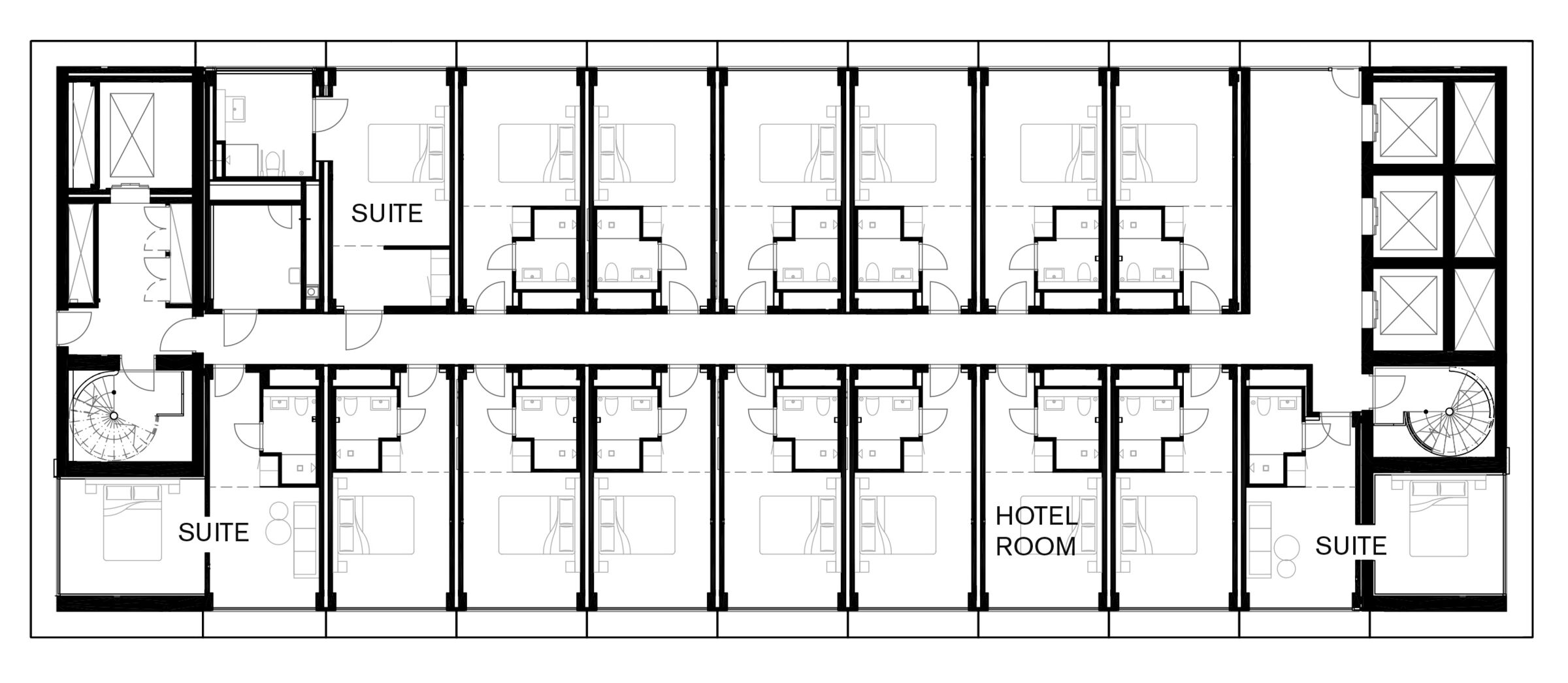

The high rise consists of two cores, one at each end of the plan, between which 13 levels of the prefabricated hotel modules are stacked in symmetric rows about a central corridor. Due to the stacked nature of the modules, which also carry the weight of the facade and corridor, there are few traditional slabs or columns. The tower was constructed and stabilized in progressive 16-meter vertical sections at a speed of about half a floor per day: this approach helped to minimize the exposure time of CLT components to the weather.

One structural challenge, according to Schmitz, was meeting the stability requirements for the tower. “We needed stiffness in the building because of the lightness of the CLT,” he says. This was partially solved by integrating posts within the four corners of the modules as well as four steel brackets tying each module into those adjacent and forming a sort of structural lattice. Concrete slabs at the top two floors act as a damper to add weight and slow down the building’s acceleration resulting from wind loads.

Another challenge was designing for the shrinkage of timber over the height of the building, a dimension of some 10 centimeters. The key was ultimately to build all building structural components in timber so that the shrinkage would be consistent. “This would have been more difficult in a hybrid structure and would have required differences in the floor heights,” says Schmitz.

Consistent dimensions were important to achieving overall simplicity. The modules are consequently nearly all overdesigned: “We took the position not to vary them, that way things stay simpler in one direction,” says Schmitz. Each module takes the loads of those stacked above it, yet the modules do not become leaner or lighter at upper levels. According to Schmitz, analyses showed that the reduced costs of lesser material for varied module sizes did not outweigh the costs associated with additional complexity in engineering and construction.

A prefabricated module

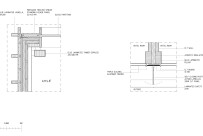

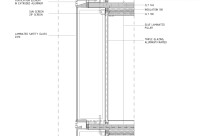

The hotel rooms are box-shaped modules, factory-assembled with bathrooms, installations and finishes. The units also included an inner layer of glass facade to make them weather-sealed. A second outer skin for increased performance was then assembled on site. Each module consists of 10 centimeters of CLT wrapped in insulation to meet Sweden’s stringent acoustic and fire requirements for sleeping units. To increase acoustic performance, the structural brackets connecting one module to the next were designed eccentric to the CLT, placed within the insulated gap between the modules. Cables for the electric system are located in the insulation cavity between modules. And both the plumbing and air intake systems are vertically stacked among units.

The CLT is overdimensioned to include an extra interior timber layer in case of future damage - from fire, for example. “You can scrape off one layer and replace it,” says Schmitz. The modules are also fitted with a redundant sprinkler system for increased fire protection.

The modules as a whole were designed according to a 3.6 meter grid, allowing two to fit on a single truck for transport. Once on site the modules were lifted into place by crane. The entire production and assembly process was regional, with a sawmill located 60 kilometers from the site supplying its timber to the local module fabricator, Derome.

An interior environment with natural finishes

The hotel unit interior is distinctly warm with simple, natural and high-quality finishes. The ceilings and walls of exposed CLT lend the space an ambience one might find in a small chalet. A single large glazed window offers each unit outstanding views to the surrounding city.

Three grades of CLT spruce finishes were available on the market, according to Schmitz, and the middle grade was chosen to balance economy with quality. The resulting exposed wood finishes are consistent with limited knots. Due to the unit length, no joints in the wood were required on the apparent walls or ceilings.

The finish layer of spruce was sanded and painted with an anti-flammable, white pigmented sealant. The paint, according to Schmitz, is barely visible and does not detract from the natural rawness of the timber. “It smells like wood in the unit,” says Schmitz. “It has faded away a little bit, but in the beginning it was like coming into a sawmill, in a good way.”