A tranquil yoga studio built with rammed stone walls and a copper shingle roof has been completed by Invisible Studio. Designed for The Newt in Somerset, the yoga studio is the third building created by the British architectural practice for this idyllic country estate and hotel.

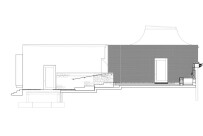

A delightful secluded retreat, the yoga studio was built in the context of the hotel’s Hadspen House, a beautiful listed building made from a warm reddish limestone. Architect Piers Taylor, founder of Invisible Studio, explains: “Hadspen’s walls, outbuildings, and garden walls are all built from the same stone. The material has been there a long time and has a feeling of permanence. It therefore made sense to use this stone for the yoga studio.” The design complements two other buildings by Invisible Studio: an adjacent gymnasium, whose walls were made using rammed stone, and a nearby exhibition space and apiary for honey bees (the ‘Beezantium’), from which the yoga studio borrows the copper roof detailing.

Building the yoga studio

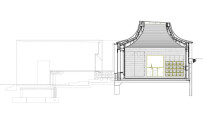

Similar to rammed earth, rammed stone is crushed and a binder is added. The Hadspen limestone was crushed to dust and a binder made using part lime and part GGBS (Ground Granulated Blast-furnace Slag) was added. Taylor describes the process of building the yoga studio’s walls: “Formwork was made from plywood in 600mm lifts. We then poured 150mm of a relatively dry mix that was rammed by hand to 100mm. There were approximately four to six pours per lift, resulting in the build-up of layers.” The external skin is cast against temporary plywood shuttering. Internally, a cavity is made using SureCav, a permanent formwork. “The external skin is tied back through the SureCav to a ply sheathing fixed to an internal studwork wall,” Taylor explains, “providing insulation and everything required to keep a building warm and dry.”

During the Covid-19 lockdown, the Beezantium’s exhibition fit-out was on hold and the building was put to use as a temporary room for yoga classes. The space, with its timber lining and large roof light, was very much enjoyed by the hotel’s clientele. As a result, the hotel asked Invisible Studio to design a dedicated yoga studio, one that was similar in style to the Beezantium. From Taylor’s perspective, he believes the client is interested in having a family of buildings that use a restrained palette of consistent and similar materials. He explains: “The Beezantium has a copper roof and uses copper detailing. Similarly, the yoga studio makes use of copper shingles and internally, copper is applied to various surfaces, including the kitchen and an area where shoes and yoga mats are stored.”

“All about that view”

The yoga studio’s interior is both exhilarating and serene. Lined entirely in beech, with the exception of one wall that is lined with mirrors, the effect is a cosy and warm, almost womb-like space. Beech was chosen for its durability, stability, and springiness. At its apex is an enormous 11m roof light, a single insulated glass unit that provides a captivating view of the sky. For Taylor, it was “all about that view” and it’s the reason why, from the outside, the yoga studio roof is expressed in what might be characterized as an ‘Irimoya’ roof-style (a Japanese hip-and-gable roof where the roof slopes down on all four sides). On the inside, the curved inner surface of the ceiling leads the eye to the roof light and beyond.

Exploring materiality and risk

The yoga studio’s three core materials — rammed stone, copper, and beech — work in complete unison to create a building that embraces nature and harmony. For Taylor, exploring the materiality of a building is always a process of research and experimentation, and interestingly, not a scientific undertaking. He describes the judgement around the rammed stone mix as one that requires an acute sensibility: “It isn’t like making cement where you simply prescribe a recipe that someone then mixes. It’s a material that is very much alive and that’s particularly interesting. You need to judge the moisture content, the aggregate mix, how hard to ram it — there is a huge amount of variability in the process and the outcome is often unknown.”

In his architectural practice, Taylor prefers working with people who are generalists and chooses to use specialists less often. According to Taylor, “the generalist is able to do a number of things, such as working with a relatively ordinary material, from which they can make something beautiful.” It is about judgement, making mistakes, and serendipity.

Taylor makes reference to David Pye, a former Professor of Furniture Design at the Royal College of Art. Pye spoke of ‘the workmanship of risk’ where the quality of the outcome is not predefined or certain (as is often the case with mass production). Taylor describes a workmanship of risk as “having a sensibility, where you cannot specify everything in advance of the construction of something.”

The yoga studio’s successful completion was a result of effort, hard work, and doing, with tasks carried out by people who understand this way of working and aren’t afraid to labour. Taylor explains: “I have realized it’s essential to have people who will make a judgement about what the rammed stone mix needs, how much water, how much ramming. They know that every lift is different. They will make mistakes, but also work out how to catch a mistake. Rammed stone is a material that has real character.”

A building that performs

The yoga studio’s environmental credentials were important in its construction. Taylor highlights two points: “Firstly, the operational carbon is low because the studio is highly insulated. Secondly, embodied carbon, which is the big challenge, is very low—it’s a structural timber frame with stone quarried on-site and a binder that combines lime and GGBS, a low-carbon cement substitute.” It is only the building’s copper elements that will have a large carbon footprint.

The yoga studio was the second time Taylor completed a rammed stone structure on the hotel’s estate (the first was the gymnasium). He felt he had learned a lot since that first project, believing the yoga studio to be “much more refined and resolved in many ways.” Today, the yoga studio is performing extremely well, with classes very much in demand. Asked if there were any pitfalls, anything he might do differently with respect to the yoga studio, Taylor replied, "it’s one of the very few buildings we’ve ever done to which I probably wouldn’t do anything differently — the only building where I wouldn’t change a thing.”