GREAT BARRIER—“the Barrier” or “the Rock,” as locals call it—is a 110-square-mile island of steep hills, surf beaches, and sheltered bays 60 miles north of Auckland, New Zealand, at the edge of the Hauraki Gulf. To the indigenous Māori, who first occupied the island around 800 years ago, Great Barrier is Aotea, or White Cloud. It got its English title from the explorer James Cook, who landed on the island in 1769 and, in his stolid, Yorkshire sea-captain way, named it for its function as a 27-mile-long barrier against the Pacific Ocean. Life on Great Barrier demands self-sufficiency. The island, twothirds of which is a conservation park, is off the grid. Rainwater is collected in tanks, cell-phone reception is patchy, and groceries are shipped in every couple of weeks. In winter, storms cut Great Barrier off for days at a time; this March, a tsunami warning sent islanders hurrying to higher ground. Even in the third decade of the 21st century, Great Barrier remains remote—half an hour from Auckland in a small plane, over four hours on a ferry—and that’s how its permanent residents, who number fewer than a thousand, prefer it. On the island, visiting the mainland is often described as going to New Zealand. Distance, however, is no obstacle to the market for coastal real estate. In recent years, Great Barrier’s modest dwellings have been supplemented by holiday houses designed by leading architecture practices, most prominently Auckland-based Herbst Architects. Over the past two decades, the office has designed 10 beach houses on the island—including the one for the firm’s founders, Lance and Nicola Herbst—and in doing so has developed its own take on a building type with strong cultural resonance.

Historically, architecture ceded the New Zealand beach to the “bach,” a type of vernacular cottage. Although fast disappearing, the bach is still idealized for the simple lifestyle it represents—in the local imagining, it’s Adam’s house in Paradise. For architects designing a Great Barrier beach house, the challenge is to evoke the bach’s relaxed spirit while meeting the expectations of affluent clients.

The Awana Beach House is the latest in Herbst Architects’ series of Great Barrier holiday homes. The house, designed for an Auckland couple with two young children, sits alone in the dunes above a public beach. In the design, the architects implemented their now-familiar beach-house strategy of layered protection, an approach that deploys screens and shutters to achieve a balance between shelter and privacy, on the one hand, and connection to the site and wider context, on the other.

Including the covered front deck and entry boardwalk, the steel-framed house is 3,440 square feet in area. A separate 640-squarefoot garage houses batteries for storing the power produced by rooftop solar panels, as well as a backup generator. (Last year, the generator was needed for only 60 hours.) On a concrete pad, two single-story rectangular forms meet like the top and tail of a T. The concrete living wing runs roughly north– south, facing the beach; the timber-framed bedroom wing is aligned east–west behind it and, like the adjacent boardwalk, is elevated 6 feet to accommodate the slope of the terrain.

The house’s wings intersect in the “lanai,” a 1½-story volume central to the plan and the program. This covered courtyard, with a fireplace allowing year-round use, opens on its north and south sides, bringing the outside in. Herbst Architects’ beach houses have always presented plenty of options for physical en - gagement with the natural environment. At times, these suggestions could be quite point - ed: in early Herbst houses on the Barrier, a trip to the loo might mean a dash through a downpour. Nowadays, clients requiring great - er amenity are unlikely to seek such an adven - ture. The Awana Beach House offers sensory experience through material specification— sections of board-formed concrete that give texture to the kitchen, living space, and lanai; the eucalyptus pilularis that lines the ceilings; and the pale timber of the native tawa tree used as flooring.

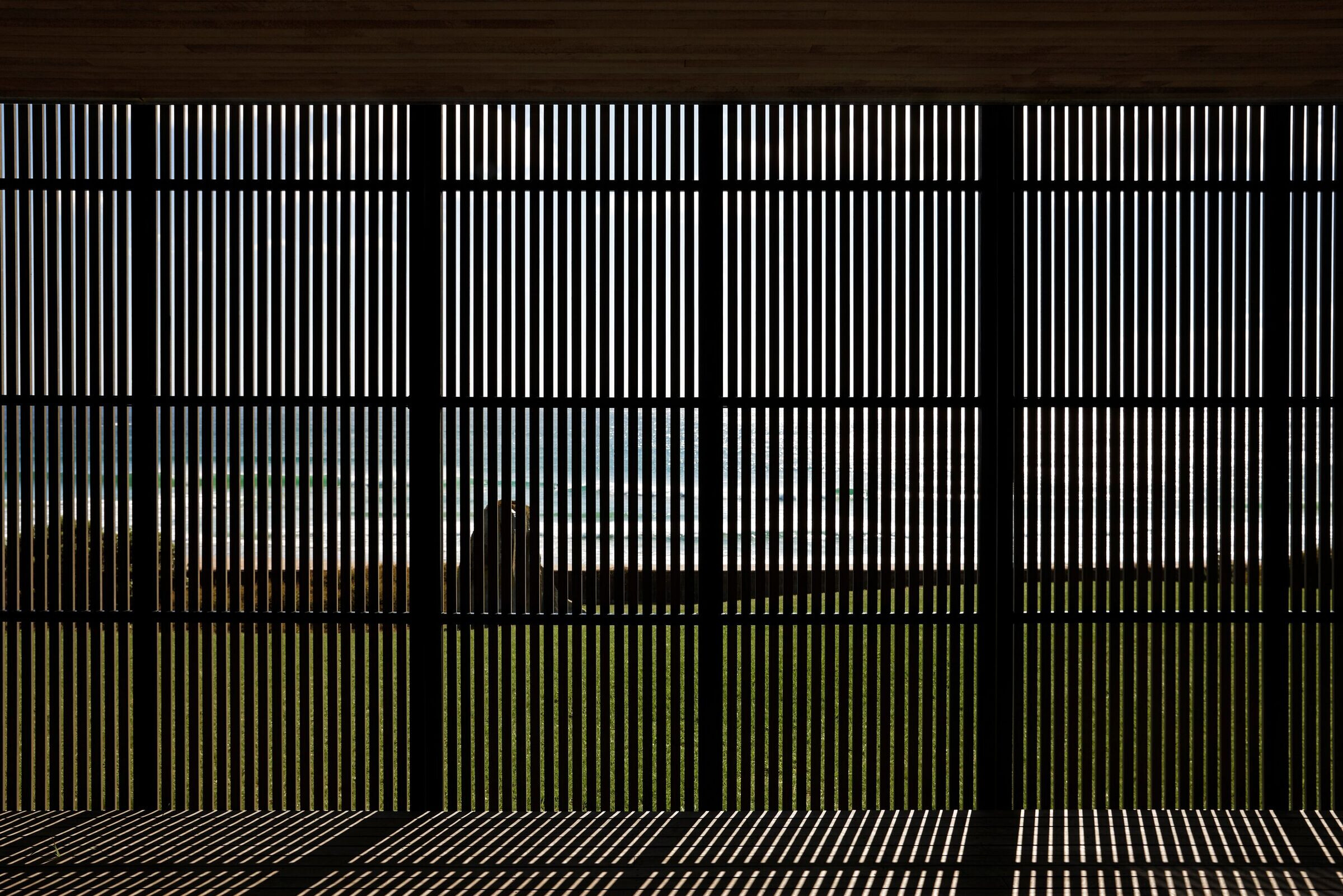

What utterly separates this beach house from any bach is its detailing, exemplified by the tracking system, in aircraft-grade alumi - num, for the sliding doors, shutters, and banks of cedar battens. These weathered gray screens, 10½ feet high, extend from the floor to the building parapet, providing a first line of weather defense and enabling the house to blend in with its surroundings and defer to the Barrier’s unflashy sensibility.

“We didn’t want heroic modernism,” Lance Herbst says, “but a house that is low, recessive, and designed to be viewed when closed down—a house demanding in its detailing, not its form.” The contractor, who has worked on the island for more than 30 years, often with these architects, knew what to expect. “The Herbsts are very particular,” says Great Barrier Building Company’s Johnny Scott, with a builder’s diplomacy. “But I do like working with them.”